Examining the Discourse of Politics in Video Games

People know what they do; frequently they know why they do what they do; but what they don’t know is what what they do does.

— Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason

Humans crave stories. We naturally gravitate towards narratives in our media to inform us, entertain us, and emotionally resonate with us. It is through those narratives we encounter in our daily lives that informs both our worldview as well as our perspective of ourselves. Most commonly though, we use the wealth of entertainment media available to us as a means for escapism. We often use these fantasies as a means to escape the stress and frustration of the real world. However, whenever aspects of the real world start to seep into our escapist fantasies, it can break that escapism.

But what exactly is politics? Politics can mean so many different things since there are many kinds of politics. There are partisan politics, geopolitics, economical politics, social politics, identity politics, etc. The list can be extensive as you wish it. Whether we are conscious of it or not, politics are present everywhere in our media, even in our entertainment. According to French philosopher Michel Foucault, he argued that the discourse around politics is rooted in the concept of power. In his book, Politics of Truth, he wrote, “We should not understand the exercise of power a pure violence or strict coercion. Power consists in complex relations: these relations involve a set of rational techniques, and the efficiency of those techniques is due to a subtle integration of coercion-technologies and self-technologies” (Politics of Truth, 155). What Foucault is getting at is that politics is the language of power. It is how the stories we equally love and hate attempt to influence our worldviews. In a sense, any form of art with a specific worldview is political, and this gets complicated when it comes to video games.

Discussing politics and video games is viewed as a sort of contradiction by some. Common wisdom argues that video games are meant to be fun, so why would you ever want to talk about politics? Politics ruin the escapism. However, I see video games as a unique form of art and media. While most other forms of media like books and film ask their audience to be passive observers, video games are more akin to theater or concerts, where the audience becomes an active presence of the art. The audience has a chance to actively engage and participate directly with the politics and themes of the game. I believe this creates more of a lasting impression upon the player. It’s one thing to watch how politics play out in a movie, but it is a whole different experience to play an active role within those politics. What I hope to accomplish is to examine not just the exact politics in games, but also examine the reaction of the gaming community.

All Fun and Games

Politics can be, understandably, a messy topic to discuss, and this is especially so when it comes to video games. When I spoke to gamers about their thoughts on politics and its presence in video games, there were a wide range of reactions to the topic. One such gamer I spoke to is Robert, an undergrad student studying game design at East Tennessee State University (ETSU). He also had taken over as the president of the local video game clubs at the university in February 2018. From Robert’s perspective, politics in games include modern trends and themes that are implemented into the game’s world. One game we brought up was Mafia 3, an action, crime game set in a fictionalized New Orleans during the height of the Civil Rights Movement. Players took control of Lincoln Clay, an African-American man who has just returned home after fighting in the Vietnam War. The game is heavy with its themes of institutional racism in its narrative, and the gameplay reinforces it. The game early-on lets the player know that the police will be deliberately slower to respond to crime carried out in predominantly African-American neighborhoods, demonstrating the institutional racism at play in the world.

“Players want to escape through their games,” Robert explained when I asked him why some gamers have negative reactions to these kinds of politics. “And when they see modern issues in their games, it breaks that escapism.” When Mafia 3 released, it received in equal parts both praise and criticism for its subject matter. While some praised the game for its themes and characters, others criticized the game in how gamifying such serious subject matter can inadvertently trivialize its depiction of racism. Within the gaming community, we also saw heated arguments about the subject matter of Mafia 3.

Since Robert acts as the head of ETSU’s gaming community, he understands how these political discussions can get out of hand. “We have a rule where politics should not be discussed at the club. This isn’t because we want to suppress free speech, but it’s because we want to create a welcoming environment. Heated political discussions can deter people from participating in the club.”

While there are certainly groups of vocal gamers that oppose politics based upon the politics themselves, there are others who are simply exhausted of seeing these political themes pop up constantly in their games. “Politics are everywhere anyways, and it feels like the same thing over and over, and I’m just getting tired of it,” responded Sarah, a 21-year-old white gamer, whenever I asked her about her view on politics in games. For her and many others, it is not so much that she is against politics all-together in her games, but rather she feels that games that include politics are often overly explicit with their political bias and lack anything new that they bring to the conversation. Sarah further elaborated on her point, saying “Games with political bias typically piss me off. It’s in your in face, like some sort of 90’s tv commercial.”

This exhaustion is not at all uncommon for players. I spoke with Greg Marlow, an assistant professor at ETSU who teaches animation and modelling to aspiring game design students. He also previously worked four-and-a-half years at Firaxis Games, a video game studio known primarily for their Sid Meier’s Civilization series. When I asked him why do some gamers oppose politics in their games, he answered, “I think that sometimes the player wants an experience that’s not going to challenge them in that way. They may feel duped if they bought a game thinking like that, and then it’s bringing things up where they go, ‘ugh don’t I get enough of this in the news?’ I understand that exhaustion wanting something that’s not going to make me think about that right now.”

Politics are everywhere anyways, and it feels like the same thing over and over, and I’m just getting tired of it

-Sarah

However, Greg also adds, “I think on that level, you just buy a different game. There are games that are not going to make you do that.” Greg makes a point that it is ultimately the player’s choice to engage with those politics, and if they feel the game has too much politics, there are plenty of other options available to them.

Playing with Politics

So exactly how do players engage with politics in their games? It may not be so simple as someone might think. Games ask players to take an active role in its ideologies. When I spoke with Sergio, a 19-year-old Hispanic gamer, he recounted his own encounter with politics. When he played this year’s newest Call of Duty game, Modern Warfare, he was surprised when he played the level, “Clean House.” Call of Duty has always been criticized for its depiction of human violence and war, as the series often took real-world analogues of conflict and translated them into power fantasy set pieces for the player to experience.

“Clean House” is different from other Call of Duty levels as rather than testing a player’s ability to react quickly and shoot hostiles, it instead places the player in a tense situation where their ability to assess the situation is of importance. The level opens with a squad of SAS soldiers infiltrating an apartment complex in London. Inside the complex is a terrorist cell suspected of an attack carried out earlier in the game. As the player slowly and carefully make their way through the building, uncertainty is high. Everyone in the building is in civilian clothing, and for the first time in the Call of Duty franchise, there are female hostiles present. The line between a civilian and a threat is blurred in this mission, and the player has to be conscious of their actions and their consequences. At one point in the level, as the player opens up a door, a figure dashes across the room. Is the person running to hide or go for a weapon? As the player enters the room, they see it is a woman running over to a crib to protect her child. It is possible for the player to actually kill that civilian.

“In the ‘Clean House’ mission, it makes you think what is okay or not okay,” Sergio told me about his experience. “There were several times in encounters with people I had to consider whether or not to take the shot.” What we see here is how a game is able to use its environment to reinforce its particular political viewpoint. When I asked how Sergio felt playing this mission, he emphasized how “stressed” he felt in that situation and that it made him reflect on another perspective on how armed conflict is conducted.

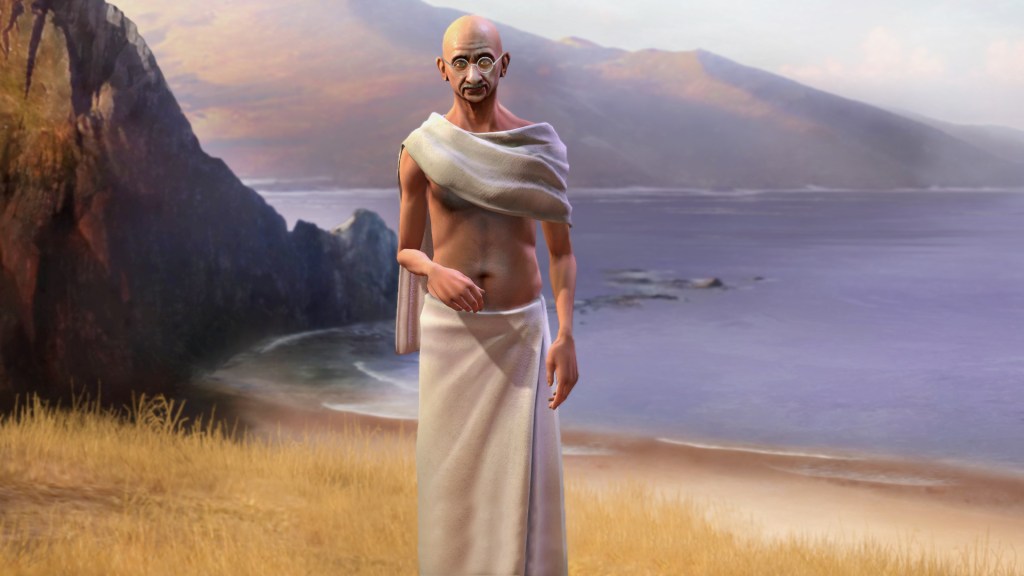

While the game did have a political impact on him, Sergio did note that on subsequent playthroughs of the same mission, he did not feel as stressed as he knew then what limits he could push the game to. The immersion of the game is broken whenever a player deviates from the developer’s intention, and any sort of political message is lost in the process. How a player interacts with a game’s themes is a tricky place to navigate. Greg Marlow brought this up in our interview as he stressed that while allowing the player the freedom to experience the game the way they wish to, there is also a catch. Greg brought up that once the game is in the player’s hands, developers have to be careful of what tools they give the player and how they can potentially manipulate it. In Sid Meier’s Civilization V, for example, players create their own civilizations and decide how that society can flourish. Players often choose from real-life historical figures to play as, such as Genghis Khan or Cleopatra, and decide the method of how their society will grow. Players can decide if they wish to grow economically, diplomatically, or even through military force.

However, Greg points out that at Firaxis Games, they were careful about which historical figures to represent in their games. “We were always trying to be respectful to the civilizations and the cultures as much as possible. Like, we never wanted anybody to be a two-dimensional character… However, it was understood that there were characters that were iconic in a bad or detrimental way to the game… For example, Hitler will never be a character in a Civilization game. There is nothing good that can come from that.” Game developers are conscious that players will manipulate their games to the max, and they have to be careful in how players may introduce unintentional politics and ideologies into their games. As Greg also puts it, “An artist has something inside their head, and they are trying to get that idea into someone else’s head, but because of how communication works, that is never going to happen perfectly.”

The relationship between player and game is informed by the experience the game is trying to give to the player versus the experience the player creates for themselves. It should be noted that most of the time, these two viewpoints on the experience of the game are not naturally opposed to each other, but at times they do conflict. I spoke with Dr. Eric Detweiler from Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU). He is an assistant professor who also teaches a “Video Games as Literature” class for undergrad students. One topic we discussed was the relationship between players and developers and how the player experiences the game. Eric said that on players and how they interact with the game, “I think one of the things that get tricky with games is that you cannot anticipate what the players are going to do with them… You can see in cases in multiplayer gaming where players mod games wildly to do things they were never originally intended to do. Unlike in a movie, you can’t control what that narrative would look like. So much of it is up to what players would do with it.” Modding is how gamers on computers can mess around with the very code of the game to change whatever they wish and even put in content they have created themselves into the game. The modding scene has created entire communities online that work with each other to create and share player-generated content for their favorite games. However, as Eric points out, this can be potentially abused and integrate harmful content such as hate speech into a game that was never intended to have that sort of message.

The gaming community have a strong voice within the gaming industry, and as Eric points out, these companies are very aware of that. “At this point, especially with bigger game companies, they are very much aware of the potential toxicity and backlash that can come from players.” Video game companies have to be careful in how they conduct their relationship with their player base, especially with the Internet and social media, the social boundary between developer and player has narrowed. I spoke with Simon, a 22-year-old white gamer, and he lamented how cautious companies have to be with their subject matter, stating, “No matter what you do, as soon as you put in a political element in your game, your actions will be interpreted as political, and this is because the interpretation is open to the player…It feels like most games are too afraid to approach topics like philosophy and politics because they are afraid of the backlash. When games start relating to topics in real-life, like religion, it infuriates people and it’s complicated.”

While video games do borrow themes and images from the real world, companies are also careful to state they are not political, or at least attempting to be not explicitly political. However, Ubisoft, a massive video game developer and publisher, has been criticized heavily in the past for including politically charged imagery without delving deeper into those topics in their narratives. This includes games like The Division 2 which is set in a tumultuous Washington D.C., or Far Cry 5, which is set in a rural town in America that has been taken over by a religious militia. In an interview with The Guardian, Ubisoft CEO Yves Guillemot defended their position, stating, “Our goal in all the games we create, is to make people think. We want to put them in front of questions that they don’t always ask themselves automatically. We want players to listen to different opinions and to have their own opinions. Our goal is to give all the tools to the player in order for them to think about the subjects, to be able to see things from far enough away.”

What Mr. Guillemot is saying is that Ubisoft wishes to use their games as a means of conversation about certain political topics without taking a side. When I first showed this quote to Eric Detweiler, he offered an interesting insight to what this could mean. “There’s a long history of people trying to create art that is not necessarily non-political, but is at least non-partisan. So trying to create stories that aren’t readily reducible to established political viewpoints or parties, but nevertheless prompt political questioning on the parts of their readers, or players, or viewers depending on what medium you are dealing with.”

However, whenever I presented the same position to Greg Marlow, he offered a different take on this unique position. “Sometimes, in the name of selling more games, people will say ‘we’re gonna do that’ but then pretend we didn’t do that. And to me, I say own up to it, admit that you are making art.” Greg argues that, in order to potentially avoid backlash and also not hurt their potential consumer base, game companies will take this kind of position in order to protect themselves and their properties. It helps demonstrate exactly why larger game companies are hesitant to “own up” to the politics in their art.

Having a Voice in Games

When the topic of politics in video games is brought up, the conversation usually turns to diversity and inclusivity. One of the major criticisms of the gaming medium is the amount of diversity, or rather lack of, when it comes to depictions of video game protagonists. As time has progressed, we have seen greater strides for games to be more diverse, such as more female-led games like 2017’s Horizon Zero Dawn with its protagonist, Aloy. There is also the highly anticipated sequel, The Last of Us Part 2, which will feature Ellie, an openly gay female survivor.

However, this movement for greater diversity in video games has been met with anger and toxicity from some gamers, stating that such inclusions are “forced diversity” and that the players feel forced into playing these roles. Eric Detweiler offered his own views to partially explain why some gamers oppose greater diversity in games. “I think in a lot of cases you might even see spaces where people will get frustrated with games getting political when they are talking about things like having female characters in game genres that have typically been male-dominated. In those cases, if you’re looking at it from an angle that games are escapism, one person might see it as a political act. ‘Oh why do we have to have this female character in this game?’ Someone else who is female who wants to play as a female character might see that as feeding into that escapism by playing as that character who looks and feels like who they are or the character they would like to play as. It comes down so much in these cases as to who the audience is and who perceives what kind of moves as political.”

I asked different gamers about their thoughts on diversity and inclusion. When speaking with Sarah, she demonstrated her frustration towards the depiction of female characters. “I like characters like Glados or Samus or Princess Zelda. They feel more believable without their femininity being the highlight of their character. They feel more human and realistic to me.” According to Sarah, she feels that often with female characters, their femininity is the highlight of their character and that they are virtually flawless in their depiction. It makes it more difficult then to relate with these characters and see them as human.

When speaking with other gamers, they emphasized the importance of inclusion in video games. I interviewed Alexis, a 22-year-old gamer from a Latin-white mixed family. She argued that diversity helped build a more believable and interesting video game world to experience. Alexis stated, “I think it’s unfair and unrealistic to always assume everyone in your life is going to be straight or white. Adding diversity makes the world feel more immersive.” She then pointed to the success of Uncharted: Lost Legacy as an example of inclusion. The Uncharted series in the past has featured Nathan Drake, a straight white male rogue, as the primary protagonist. However, in Uncharted: Lost Legacy, the game featured Chloe Frazier and Nadine Ross as the two female protagonists of the game, and Alexis pointed out how they proved to be interesting characters without falling into heterosexual norms.

One of the important aspects of diversity in video games is to acknowledge that there is a wider, more diverse base of players who wish to experience these games and see themselves represented. When I spoke with Ian, a transman gamer, he told me why he felt politics and diversity have a place in video games. ” Politics are supposed to be the ideas that help society choose what they want to be known for as a nation. So it’s important that video game companies use their money and influences on our youth to normalize diversity and provide positive representation of the people.” While we have seen greater representation of female and gay and bisexual characters, there is still a lack of characters that provide representation for the trans and gender queer community. Both Alexis and Ian pointed toward Bioware games for their greater representation of genders and sexualities in their games. Bioware is popular for their role-playing games (RPG) and allowing their players to create their own characters and decide upon their sexuality. Ian in particular focused on Bioware’s Dragon Age: Inquisition and Bioware’s inclusion of a trans male side character. “Everyone who plays a game wants to see themselves immersed into that world. A big reason why I continue to play Dragon Age is because of the representation. In Inquisition is the first accepted trans character I’ve personally seen in a video game. I’d probably play more games that are made with diversity than I would something that only shows the world through the common white male hero’s eyes.” The character in question is Krem, a trans male warrior who is the lieutenant of a mercenary group that join’s the player’s army. He is a notable example because he is the first trans character to appear in a Bioware game.

Even if it’s unintentional, any form of art with a world view presents a political viewpoint. Anything that depicts people will be political.

-Kylan

However, the fact remains that in the AAA space of gaming, there is still a lack of trans and gender queer representation. I also spoke with Kylan, a transwoman and gender queer gamer, about her thoughts on representation. She asserts that representation in the larger gaming market has been restrictive for the trans community, as while there have been trans characters in AAA gaming, they are typically found in minor roles and never the protagonist. “If I saw a game where I could play as a trans woman, it would be wonderful,” Kylan asserts. “There has been decades of being forced into a cis white hetero male as the protagonist, so having characters beyond that as the norm is amazing.” What we determined is that where the AAA space of gaming lacked trans representation, the indie market is more likely to be inclusive. For example, the indie hit RPG Undertale features a protagonist whose gender is never specified, leaving it open to the interpretation of the player. I also spoke to Kylan how some gamers have a negative reaction to politics in their games, and she stated, “Being able to ignore politics without consequences is valid, but it is also a form of privilege.”

My Story

I understand the argument for wanting games to be simply escapist fun. For a long time, I used to think of games the same way too, often distancing myself from the politics that arose in the games I played. Players just want to have fun. Yet, one of the most powerful and visceral moments in gaming for me was an experience that filled me with dread and physical sickness. Spec Ops: The Line was the game that helped me realize the narrative potential of video games and how they can effectively engage their players with their politics.

Spec Ops: The Line was a game that was built to appear on the surface as a normal shooter game akin to Call of Duty or Battlefield. However, unlike many of the games we mentioned from earlier, Spec Ops does its damndest to break the immersion of the game. Whereas most video games focus on drawing its players into the virtual world they craft, Spec Ops focuses on drawing attention to its own un-reality. One of the unsettling ways it accomplishes this is through its use of loading screens. Typically, loading screens are meant to provide hints and tips to help the player progress through the game. However, Spec Ops uses loading screens as an opportunity to speak directly to the player, stating things like:

- How many Americans have you killed today?

- To kill for yourself is murder. To kill for your government is heroic. To kill for entertainment is harmless.

- If you were a better person, you wouldn’t be here.

- Cognitive dissonance is an uncomfortable feeling caused by holding two conflicting ideas simultaneously.

Unlike other shooters, Spec Ops: The Line focuses on the horrors of war, violence and the trauma it leaves behind. Whereas many players would typically dismiss these messages by stating “it’s just a game,” Spec Ops takes away that argument by making it very clear that it is aware it is a game. Instead, the game directly questions the motivations of the player, of why they would even start to play a game like this. What kind of person seeks escapism and entertainment by harming and killing others in their fantasy? In the closing moments of the game, Spec Ops speaks directly to the player over a montage of all of the violent acts the player committed up to this point, stating, “The truth is that you’re here because you wanted to feel like something you’re not: a hero.”

Spec Ops: The Line is a difficult game to nail down exactly how I felt about it. I can safely say that I did not have fun while playing it, but ultimately, I’m glad I did. It was a game that had left its mark on me, a game that made me uncomfortable to play other games for literal months. Even now, 5 years after my initial playthrough of that game, it is the piece of media that sticks out most in my mind and nearly colors anything I have played since then. Spec Ops is a game that does not shy away from its politics, and instead fully embraces it. Its a game that proves that video games can do so much more than be fun. It is certainly not my favorite game, but I feel it is the most important game I have ever played, and if we were to remove politics from our games, it would sadden me to see less Spec Ops’s in the world.